As I’ve mentioned before, when it comes to competing to be one of the European Union’s new natural gas suppliers, Senegal and Mauritania have several advantages.

One, they have geography on their side. Their location should make it easier and more efficient to deliver liquefied natural gas (LNG) to regasification terminals in European port cities than it would be for other, more distant African nations, such as Mozambique, which is slated to begin LNG production later this year.

Two, they have demand on their side, as the EU is eager to build up a more diverse roster of multiple suppliers, each capable of replacing part of the large amount Russia has been delivering on its own. Senegal and Mauritania are set to begin production when Europeans’ memories of anxiety over fuel supplies are still quite fresh, so they will be in a good position to establish a solid business relationship. This creates an obvious edge for Senegal and Mauritania, as strong demand generally lifts prices.

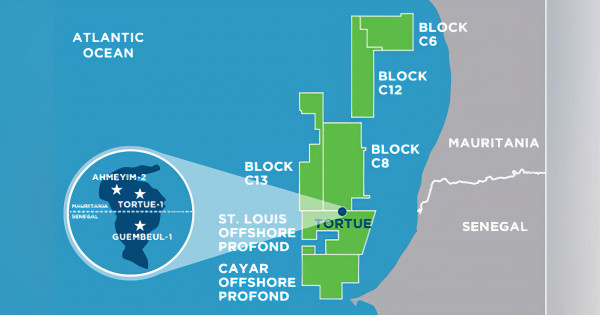

And three, they have timing on their side. EU authorities want to see the bloc’s Russian gas imports come down by two-thirds before the end of this year, and Senegal and Mauritania are scheduled to bring their first export-oriented gas project, Greater Tortue/Ahmeyim (GTA), online in the third quarter of 2023.

But this combination of advantages won’t be permanent. Granted, the geography won’t change. We can assume the distance between Dakar and Europe will stay the same during our lifetimes. But gas demand and the timing of new greenfield projects will change. The EU won’t always be conducting such a critical search for new gas suppliers as it is doing right now, and African gas producers won’t always be launching new fields at such propitious moments.

Accordingly, Senegal and Mauritania ought to be doing some big-picture thinking. As we state in our soon-to-be-released report, Petroleum Laws - Benchmarking Report for Senegal and Mauritania, these countries should be asking questions, not just about how to use their resources to meet the needs of the moment but also about how to optimize their resources and maximize returns over the long haul.

Here are two of the big questions that I believe are worth asking — and the answers the African Energy Chamber (AEC) would give.

Are Gas Development Plans Primarily Focused on Exports, Or Do They Also Make Provisions for the Build-Up of Local And Regional Gas Markets?

Without a doubt, the Chamber believes that African gas projects should have as many African components as possible. That’s why we favor partnerships between international oil companies (IOCs) and their African counterparts — partnerships that involve training programs and skills and technology transfers. That’s why we favor local content policies that are designed to support service companies in sectors where African providers have and can obtain advantages.

That’s also why we favor the establishment of gas-based industries within Africa. We believe that gas-producing states should have the right — and the opportunity — to use their own resources not just to earn foreign exchange, but to transform their own economies.

So as Senegal and Mauritania work with IOCs to move gas development and exports forward, they should also be making plans for domestic gasification. They should be thinking about bringing gas onshore, where it can be used as fuel for power plants, as a source of energy for industrial facilities, and as a source of feedstock for petrochemical plants. These are all things that can create jobs, eliminate energy poverty, and raise standards of living, thereby changing people’s lives for the better!

Fortunately, Senegal is already taking steps in this direction. President Macky Sall has already unveiled plans for using most of its share of gas production to improve domestic electricity supplies. The state natural gas concern, Senegal Gas Network (SGN) led by the former Petrosen E&P Director, Joseph Medou, has said it will build an onshore pipeline to carry a portion of the production from offshore fields to five onshore thermal power plants (TPPs) that are currently burning dirty residual fuel oil. SGN appears to be hopeful of finishing this pipeline in 2024, around the same time that work on four new TPPs is due to be completed. This is also right around the same time Senegal’s second offshore gas project (Yaakar-Terenga, once again led by BP in partnership with Kosmos Energy) is supposed to start production.

So far, so good! The AEC is genuinely encouraged by Senegal’s progress on this front to date. But it is also hopeful that the country will explore gasification programs further in the future, given that such programs can have a powerful multiplier effect on the local economy.

In practical terms, if Senegal really wants to optimize its gas resources over the long term, it ought to act now to make gas the mainstay of its own economy, perhaps looking beyond electricity generation and into petrochemicals or another gas-based manufacturing sector. And it should make certain that BP and the other IOCs working in the country’s offshore zone provide the right kind of help to make this happen.

Do Gas Development Plans Have the Flexibility To Respond to Future Shifts in World Energy Markets?

Once again, the AEC believes it’s not enough to plan for the needs of the moment. Africa’s newest gas producers also have to look ahead and think about how they can optimize their resources in the decades to come, when world energy markets will be driven by forces beyond current factors such as Russia’s war on Ukraine.

That’s why it was encouraging to see that Mauritania signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) last December with New Fortress Energy (NFE) on the establishment of an offshore energy hub capable of using natural gas to support the production of LNG, electricity, and blue ammonia fuel. The document isn’t binding, so it doesn’t guarantee that this project will come to fruition. But it does pave the way for the country to do several important things.

First, it puts Mauritania in a position to outfit its offshore energy hub with NFE’s “Fast LNG” technology. With this technology, the country will be able to install modular units on a jack-up drilling rig or another type of legacy marine infrastructure to establish a mid-size gas liquefaction plant – and it will be able to do so far more quickly and cheaply than it would if it opted for a more conventional solution, such as an onshore LNG plant or even an FLNG vessel like the one BP and Kosmos will be using at GTA. What’s more, it will be able to scale up LNG production if it chooses to do so by installing additional modules. As a result, Mauritania won’t just be just another producer and exporter of LNG; it will also be a low-cost producer and exporter of LNG with the flexibility to respond quickly if rising demand justifies additional investment in production capacity.

Second, the MoU makes provisions for expanding Mauritania’s domestic electricity supply. It calls for the offshore energy hub to deliver gas to Nouakchott Nord, an existing 180-MW TPP in the capital city of Nouakchott, and also to a new 120-MW combined-cycle TPP that the national power provider Somelec is planning to build. With this new generation capacity, Mauritania will be in a position to offer its citizens a better life — and offer job-creating businesses a more attractive operating environment. Moreover, by emphasizing gas-fired power generation, it will be able to reduce pollution. Currently, the main fuel of the Nouakchott Nord plant is residual fuel oil (RFO), which burns much less cleanly than gas.

Third, the project may be based on natural gas, but it also looks ahead to a fuel of the future – and by that, I mean ammonia. As mentioned above, the energy hub will have a blue ammonia unit, in which natural gas will be used as feedstock for the production of ammonia. This facility will help establish a market for ammonia, thereby laying the groundwork for future production of green ammonia – that is, ammonia manufactured using green hydrogen produced from renewable energy.

Mauritania stands to benefit from this expansion of its renewable resources capabilities, since it has tremendous solar and wind potential in addition to substantial gas reserves. The benefits may not be immediate, since it will take more time to realize that potential, but they could be very substantial indeed – especially if the country achieves its goals of bringing the share of renewables in the energy mix up to 50% by 2030 and developing multiple large-scale green hydrogen and ammonia projects.

Senegal And Mauritania Are Looking to The Future

Overall, Senegal and Mauritania deserve praise for their approach to gas development.

Not only are they on track to become two of the first new gas producers in Africa to join the list of the EU’s gas suppliers, but they’re also taking steps to optimize the use of their resources.

They’re making plans to use their gas to produce electricity for the domestic market, not just to earn dollars on the export market.

They’re taking advantage of the flexibility inherent in new technologies offered by foreign partners such as NFE.

And they’re thinking about what comes next — what happens when the world shifts from gas to renewable energy. And for that, the AEC commends them.

Distributed by APO Group on behalf of African Energy Chamber.

This website uses cookies.